Portland neighborhoods not above the law

Editorial

Some of our neighborhood associations are pushing back on compliance with Oregon Public Records and Meeting Law, saying it is too onerous for volunteers to administer and gets in the way of “speaking freely.”

To appreciate the significance of public meetings standards, it helps to consider why we have them, particularly why they apply to neighborhood associations.

Massive federal “slum clearance” and freeway construction after World War II dislocated thousands of households across America. Scenes of residents clinging to their doorways and porches as police officers dragged them into paddy wagons were broadcast over network television.

The redevelopment projects were welcomed by governors, mayors and city councils, who saw urban renewal as sweeping away derelict buildings and failing communities to build better and more modern cities. They dismissed the resistance as emotional overreactions by a few to projects that would benefit the many. Notorious New York City kingpin Robert Moses dismissed them as mere tenants who were losing nothing; they could readily find other apartments.

This was the Civil Rights era, and members of Congress representing targeted areas demanded a better way. The people impacted had to have a voice in federally funded projects that disrupted cities. To know who was impacted, there had to be a system in which residents of a community could be distinguished from others. In the language of the time, there was fear that “outside agitators” and communists exploited disruption for their broader political purposes.

To ensure that organizations representing the people legitimately reflect the views of the community, there had to be rules and boundaries for membership, a democratic and open process in which all could participate and influence decisions.

In time, local governments came to see that such a system was valuable not only for federal infrastructure projects but as a permanent linchpin of local governance. In 1973, Oregon adopted a land-use planning system in which citizen participation was Goal One. The next year, Portland created the Office of Neighborhood Associations to not only recognize the essential role of local associations but also to provide funding to help them be effective.

In return for the money—distributed to coalitions of neighborhoods through contracts—the organizations had to operate as public bodies bound by state laws for transparency and accountability. It was not an unreasonable expectation. For all government spending, there must be a means to see that it serves the intended purpose.

Without such controls, including geographic divisions in which anyone may exercise membership rights, government funds could fall into the hands of local bosses, political operatives or those with agendas beyond representing all of their constituents.

And without “paperwork,” how can it be established that meetings were properly announced, decisions were made openly according to bylaws and that all had the opportunity to participate?

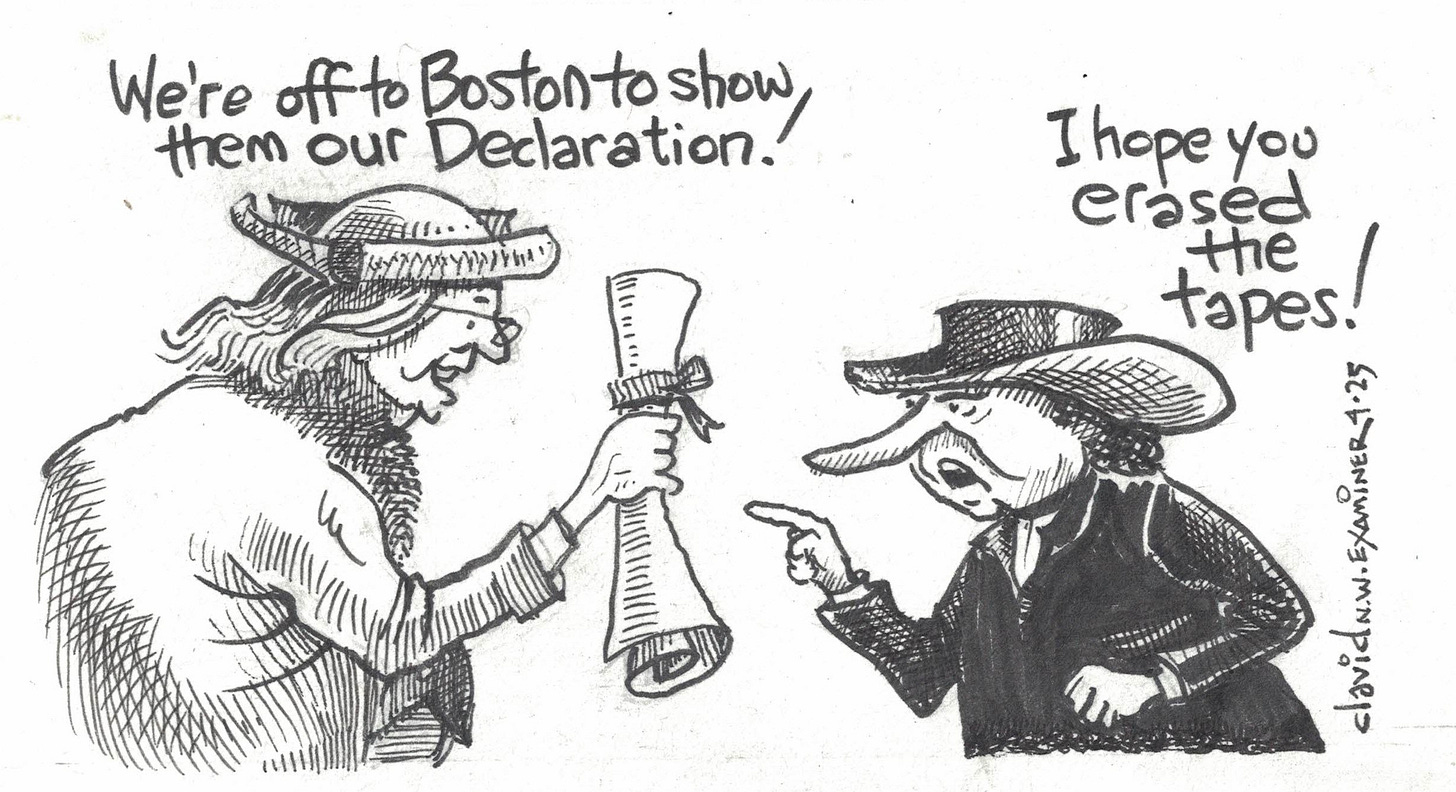

Failure to keep adequate minutes, erasure of meeting recordings and decisions without meetings are glaring signs of the breakdown in democratic accountability. The worst cases of unilateral action almost invariably are revealed by missing links in the record.

To have power over others, to speak for “the people,” entails being answerable to them. There is a duty to explain what has been done in their name and why. That mechanism restrains leaders from acting carelessly or for personal goals. No leader is perfect, but those who will not stand behind what they have done and invite the dissent or correction of their constituents are false leaders.

Some of our local neighborhood representatives do not believe they should have to face such accountability and are literally destroying the records that would reveal their words and deeds. There is a democratic solution to their usurpation if we exercise the authority we possess.

Allan, you’re assuming these NA’s in Portland really have much power. They don’t. They historically have gotten a few thousand bucks from the city per year…like $2,000. Now many are losing that funding under the city government system as it’s going to all grant funding and priority is given to POC and “vulnerable people” projects. The only way to get more $ is to have fundraisers or apply for these low dollar grants. These grants require the planned action to help certain identity groups which the city has decided are more “worthy” than others in the neighborhoods. And they’re all volunteers run. And here you are carping about public disclosure laws? All the NA meetings are open to ALL residents of the neighborhood—-just show up if you care.