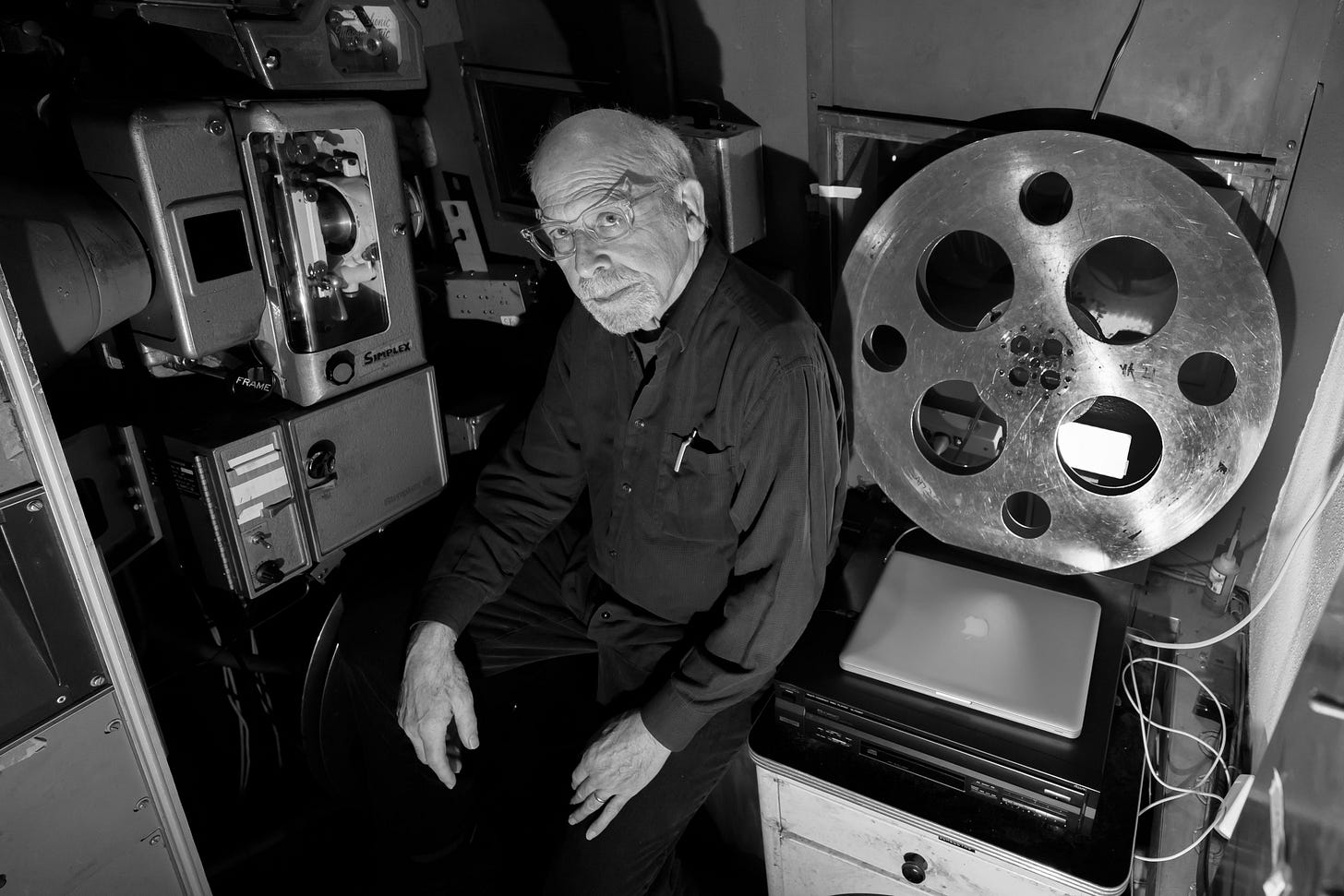

This man gets the pictures

Elliot Lavine is Cinema 21's Saturday Morning Classics programmer

You don’t have to be psychopath to enjoy film noir, Elliot Lavine assures me, then smiles and goes on to explain, but you may be “a voyeur.” He smiles again. He’s really quite amiable for a man who enjoys immersing himself in the dark, menacing, fatalistic world of film noir.

You’d be hard-pressed to find anyone in Portland more knowledgeable about film noir and film in general. Lavine programs the Saturday Morning Classics series at Cinema 21, Northwest Portland’s century-old independent theater.

Lavine is a San Francisco transplant, and we are fortunate that after roughly 40 years he tired of the Bay Area — “too expensive, too crowded, not what it once was.” Still for much of his time in San Francisco, Lavine was the film programmer at the Roxie Theater, one of the oldest movie theaters in the United States. If you know indie movie houses, you’ve probably heard of the Roxie, located in San Francisco’s Mission District. For decades, Lavine chose the iconic theater’s films, based on his finely-honed tastes. His departure in 2016 was news. The San Francisco Chronicle wrote that San Francisco’s loss is Portland’s gain. The paper called him a legend in Bay Area film circles, saying “Lavine may just be the last — and best — of a dying breed.” Most movie theaters belong to national or regional chains, and corporate programmers choose the films they show. Few theaters employ their own programmers with a deep knowledge of filmmaking, film history and film aesthetics. This is where Lavine comes in — every Saturday morning at 11 at Cinema 21.

Lavine started the Saturday series five years ago with Cinema 21’s owner, Tom Ranieri. (The two men had known each other for years. The world of independent art houses is small.) First, the classic films were shown just once a month — it wasn’t clear there would be a following, but it turns out there was and now the classic films are shown weekly. Each month, Lavine selects a different theme. Hitchcock just wrapped up. Ranieri says nothing sells tickets like Hitchcock.

Last year, 400 people came out to watch Hitchcock’s “Rear Window.” That filled 80% of the seats in Cinema 21’s 500-seat theater. When was the last time you saw a movie — that wasn’t a blockbuster — with that kind of crowd? According to industry trackers, most theater owners are lucky to regularly fill between 10 to 20% of their seats. But even the typical attendance for Saturday Morning Classics outdoes that. Turnout for the classics consistently puts 150 paying customers in Cinema 21 seats— meaning a good one-third of the seats are filled.

In the age of streaming, Lavine still knows how to do the formidable — get people to leave their homes to go see a movie on a big screen with a bunch of strangers. No surprise. Lavine says seeing films on television, laptops, iPads, iPhones just doesn’t cut it. Films that were made for the big screen should be seen on the big screen he says — because that is the only way the audience can see everything the director intended them to see. (Don’t think Lavine is one of those baby boomers who constantly rails against 21st century technology — every quarter, he teaches a film class at Stanford over Zoom.)

After all these years of film programming, Lavine still gets a kick out of sharing his love of film. Saturdays, he usually asks folks in his audience to raise their hands if they have never seen that day’s film, and he’s delighted when half the audience or more shoots up their hands. Happy too, seeing young people coming to watch the classics in a “picture house” that may have first played the very same movie before their grandparents were born.

Lavine’s passion for film began in 1954 with the movie, “Them.” While other 6-year-olds in darkened movie theaters covered their eyes when the 12-foot-tall screeching mutated monster ants came on screen, Lavine loved it. He laughs when he says this, saying he enjoyed the feeling of being scared. Even as a young boy, Lavine knew instinctively that the real world was far more terrifying than those monster movies on the big screen. And that’s when Lavine says he became obsessed with cinema. It would be years before he made the leap from that first black-and-white horror film to film noir, but you can see the trajectory.

Lavine is largely self-taught. He did attend San Francisco State briefly in the ‘70s, but mainly he got his film school education by just going to movies. Arriving in San Francisco from his native Detroit during the height of the counterculture, Lavine found a creative city with indie art houses in almost every neighborhood. You could see a movie for a dollar. For a film buff like Lavine, it was bliss. Eventually, he ended up at the Roxie, where he made a local and national name for himself as a film programmer. In 2010, the San Francisco Film Critics Circle gave him an award recognizing his work reviving rare archival titles and bringing about a renaissance in the appreciation of film noir.

Lavine is lauded for bringing attention to often neglected films, film noir or otherwise. Part of Lavine’s reputation comes from his zeal in pursuing hard-to-find films. For years, he tried to track down a copy of a little-known film called “Ride the Pink Pony.” The 1947 film noir tells a story of crime and postwar disillusionment. He also spent years tracking down a low budget early ‘60s mobster film called the “Blast of Silence.” Some prints were lost. Others got tied up in legal limbo. Both movies found new audiences once he “premiered” them at the Roxie. Lavine’s current holy grail is a 1953 American film called “Pickup On South Street” — noir with Cold War espionage. If he does finally hunt it down, you will no doubt see it at Cinema 21.

Whether it’s a crime or psychological thriller, Lavine’s love of film noir is deep-seated, and deeply felt. He interprets film noir this way: It “unlocks a dark corner either in your imagination or your subconscious.” The look is usually dark, and stark, yet shadowy. It communicates the mysterious and the sinister. There’s always a sense of dread.

Film noir, according to Lavine, brings you a world that “defies your very understanding or participation. You’re watching somebody’s demise, their self-destruction, and you’re thinking the whole time there but for the grace of God, go I. I could have made that same stupid mistake, but I didn’t, but this guy did, and now I can sit back and watch it because it’s not me.” Lavine finds comfort in that, and perhaps, we all can?

Film noir (French for black film or dark film) started in the 1940s. One of the greatest film noirs according to Lavine is “I Wake Up Screaming.” The 1941 noir has it all: murder, double-dealing, love entanglements and Betty Grable in a dramatic role. (Who knew Grable did more than comedy and musicals?) Another noir Lavine thinks may be the best of all — is a very low-budget independent film from 1945 called “Detour.” He also likes “Out of the Past” from 1947 — murder, blackmail, a doomed leading man and a sexy, treacherous femme fatale.

While these classic film noirs may be his favorites, there are plenty of modern films that also thrill Lavine. He’s seen “Marty Supreme” three times, and says he could see it again and again: “Not because I’m all that interested in what it seems to be about, although I am. But there is a kinetic aspect to that movie that makes me jumpy for two and a half hours. I’m literally up and down in my seat, I’m moving around, I’m edgy, I’m feeling all these old weird neuroses coming alive.” In his opinion, that film’s director, Josh Safdie, is the best director working today.

And what makes a bad film? Well, Lavine says it’s one that bores him, people just standing around and talking. Obvious movies, or what he calls “literate” movies. And he does not like costume movies. Lavine will not be going to see “Wuthering Heights” when it comes out later this month, just in time for Valentine’s Day.

And while film noir may be his personal favorite, Lavine also programs monthlong series highlighting other genres: Westerns, romance, screwball comedies; individual decades or directors such as Martin Scorsese; and different actors. In March, two powerful leading ladies will dominate Saturday mornings at Cinema 21: Bette Davis and Joan Crawford.

Lavine is also starting to add more foreign films to the mix. This month, it’s French New Wave. “The 400 Blows,” plays on Saturday (Feb. 7), followed by “Lola” on Feb. 14, “Cleo from 5 to 7” on Feb. 21 and “Bande a Part” on Feb. 28. (See the lineup at https://www.cinema21.com/saturday-morning-classics.)

Lavine may have made his name as a film programmer, but in the early ‘80s he directed two low-budget black and white noir shorts: “Blind Alley” and “The Twisted Corridor.” One reviewer discovering “Blind Alley” called it “noir ecstasy.” Both films are dark, gritty, unsettling, with a deep sense of dread. I promise you, you won’t be bored. I watched them a week ago and my spine is still tingling. You can watch them both at https://elliotlavine.com/about/.

Portland is no San Francisco, so we asked Elliot Lavine one last question: How would he compare Portland filmgoers to those in San Francisco? “SF pales by comparison to Portland today,” he said. “Time was, back in SF, there was a repertory theatre on every corner, but no longer. Movie theaters are closing there by the droves. Portland reminds me of SF back in the ‘old days.’ Portland is a moviegoers paradise.”

And besides that, Portland has a long fabled (partly true, partly fiction) history of vice, opium dens, prostitution and shanghaied sailors. Which makes our fair city a ready-made audience for film noir, and Elliot Lavine.

Great article. Thanks.

Lavine is one of the coterie of hidden talents in Portland. I wish I had the time to take full advantage of what he offers at our beloved Cinema 21! How about a Marx Brothers revival to balance out the noir?