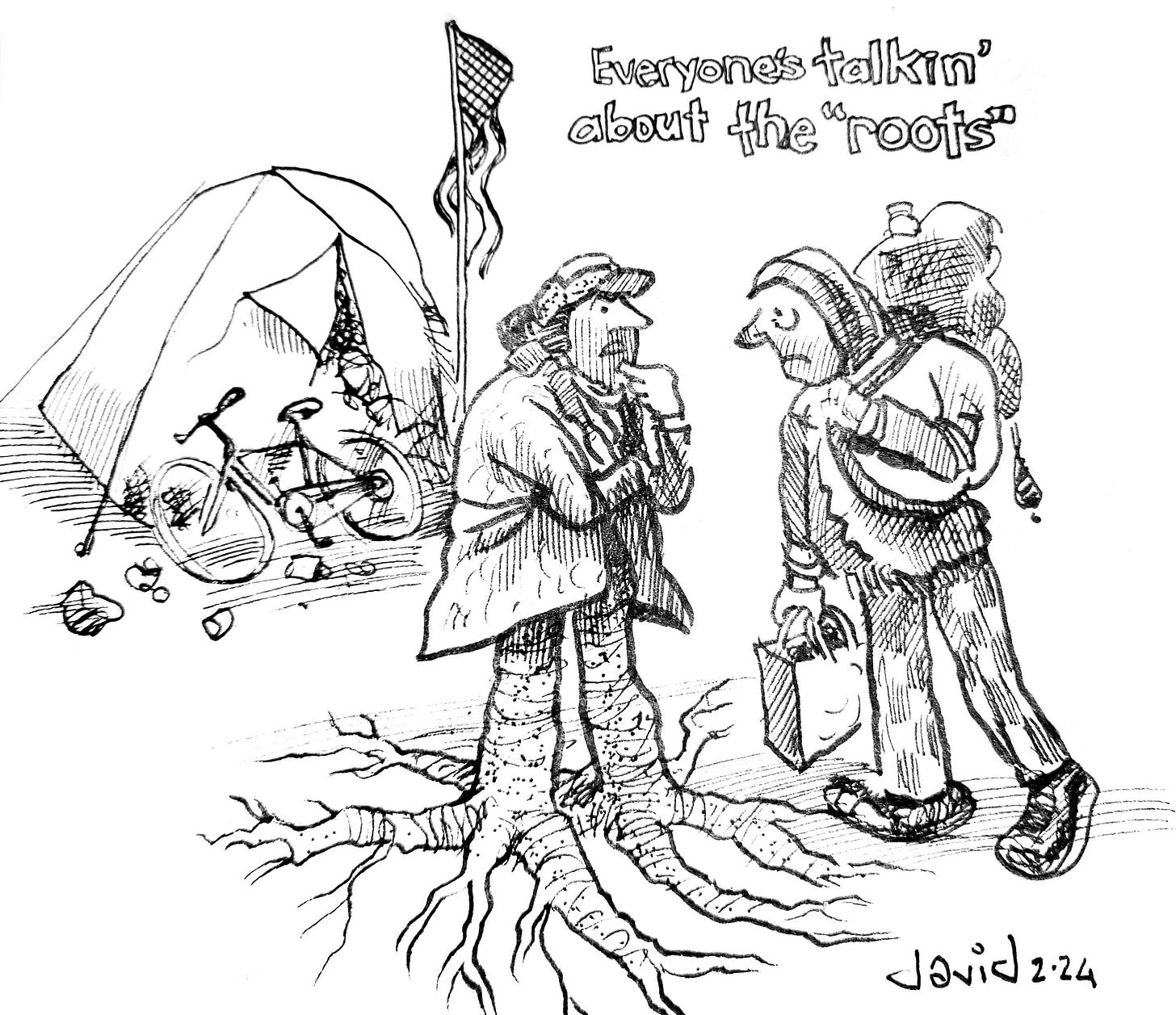

The great homelessness divide

Editorial

There are two schools of thought regarding persistent homelessness. The primary driver is either:

Lack of available housing or

Mental health/addiction.

Both explanations have validity, though adherents to each theory work from greatly different and sometimes incompatible assumptions. The best solutions should borrow from each camp, if with more emphasis on one than the other.

The worst strategies go all-in on one theory in a way that may actually accelerate the problem if they have picked the wrong horse.

The root causes of homelessness have been addressed by studies and argued high and low through anecdotes, sources I have generally found unreliable. Most studies draw from obvious bias and reveal flat-out sloppy thinking. For instance, a common survey asks what percentage of Portland’s homeless people came from outside the city and then takes whatever percentage is found as evidence of their foregone conclusion. None I have seen pose at the outset what percentage should be taken as determinative.

I cite such sophistry only to suggest that propaganda abounds and finding a consensus among experts is beyond me.

So what can one really know? Like most Portlanders, I walk streets where camping and drug usage are common. I have eyes and ears and try to make sense of what they take in. While I claim no special authority or unique information, I ask that you follow my application of broadly recognized truths.

If lack of housing were the main cause of homelessness, one would expect homeless individuals to accept almost any offer to improve their station. A heated shelter is better than a rain-soaked tent. If people are offered what they obviously need and do not take it, something else may be going on.

If mental health in combination with addictions is the primary problem, that might explain refusal to accept assistance. Dependency can be so strong that the short-term benefit of a mind-altering experience can override thoughts of a more gradual and often painful recovery process.

What do we find when campsites are swept? Only a small percentage of the inhabitants accept shelter or services. That makes no sense under Theory 1, but fits Theory 2 closely. People suffering with mental health and addiction disorders tend not to make decisions in their own best interests.

If advocates of Theory 2 minimize the importance of housing supply, the programs and interventions they recommend will still produce net benefits. The emphasis on personal recovery may diminish—but would not eliminate—resources remaining for housing construction.

Advocates of Theory 1, on the other hand, may compound the mental health and addiction epidemic. Housing-first proponents tend to hold unhoused people blameless for their plight and in no need of personal rehabilitation. Homeless people are seen as being left out in a game of musical chairs for reasons beyond their control. Involuntary civil commitment is therefore an unwarranted violation of their rights.

But if involuntary commitment ultimately provides their best chance for recovery, opposing this solution allows one cause of the problem to continue unabated.

Theory 1 depends on faith in the market to build our way out of our housing shortage, ultimately resulting in less expensive housing across the board. That requires a lot of faith and great patience when time is of the essence. Housing construction has slowed even as homelessness grows. Government and nonprofit efforts to spur and supplement housing construction are funded to the max without making an appreciable difference.

Even if housing may appear to be the best route up the mountain, finding that route unclimbable calls for course-correction.

Reasonable people of goodwill can disagree about root causes of homelessness. But none should be so certain of their inerrancy that they would undermine other approaches, which I fear is happening. Once fully dedicated to a single path, institutions become locked into a logic that demands alternative theories be discredited. They blame others or cite special circumstances when the world does not work as they predicted it would.

Our species and our societies—not perfect in foresight but capable of learning from mistakes—thrive in accordance with their ability to adapt. Our biggest blunders are often tied to knowing things that just aren’t so.