Portland housing policy's blind spot

How system development charges got a bad name

In the 1980s, Portlanders grew uneasy over runaway development. Row houses and larger mixed-use buildings were being squeezed into established neighborhoods, sometimes demolishing “good old houses” to make room for them.

Some wondered if this growth was inappropriately subsidized, underwritten by people who did not benefit from it and would prefer it not occur. Were taxes being raised, services reduced and quality of life reduced to promote investment that was making communities and the city worse off?

In 1989, the Oregon Legislature concluded that growth may not be paying its own way and enabled local jurisdictions to assess fees on builders to offset future infrastructure it triggered. The predictable burden on transportation systems, water supply and treatment, sewers and parks was deemed to justify upfront payments.

The legislation limited the scope of this saving up for the future. It did not authorize fees for expansion of schools, carbon emission mitigation or depletion of natural resources. In other words, system development charges could not be applied to a wider range possible consequences; just the most obvious and measurable ones.

Within a decade or so, development interests used the rising cost of housing construction and the shortage of affordable housing to turn the debate: system development charges (SDCs) were raising the cost of construction and therefore exacerbating the crisis in affordable housing and driving homelessness.

The truth may be too complex to conclude anything with certainty. The cycle of life has always entailed parents supporting their young children, who do not repay them but instead invest in the next generation, for instance. Perhaps in the same way, everything works out for the best in the long run without anybody keeping score.

But I am quite sure we didn’t move from “SDCs are good” to “SDCs are bad” through blind faith in market forces. Nor was it a process of research, deliberation or philosophical soul searching. The industries most impacted by SDCs reframed the public debate and lobbied their way to a new political consensus that sees these charges as impediments to pressing social needs.

What if the current thinking is ill-founded? Setting aside questionable formulas for calculating SDCs, could the absence of any process of paying ahead be unsustainable?

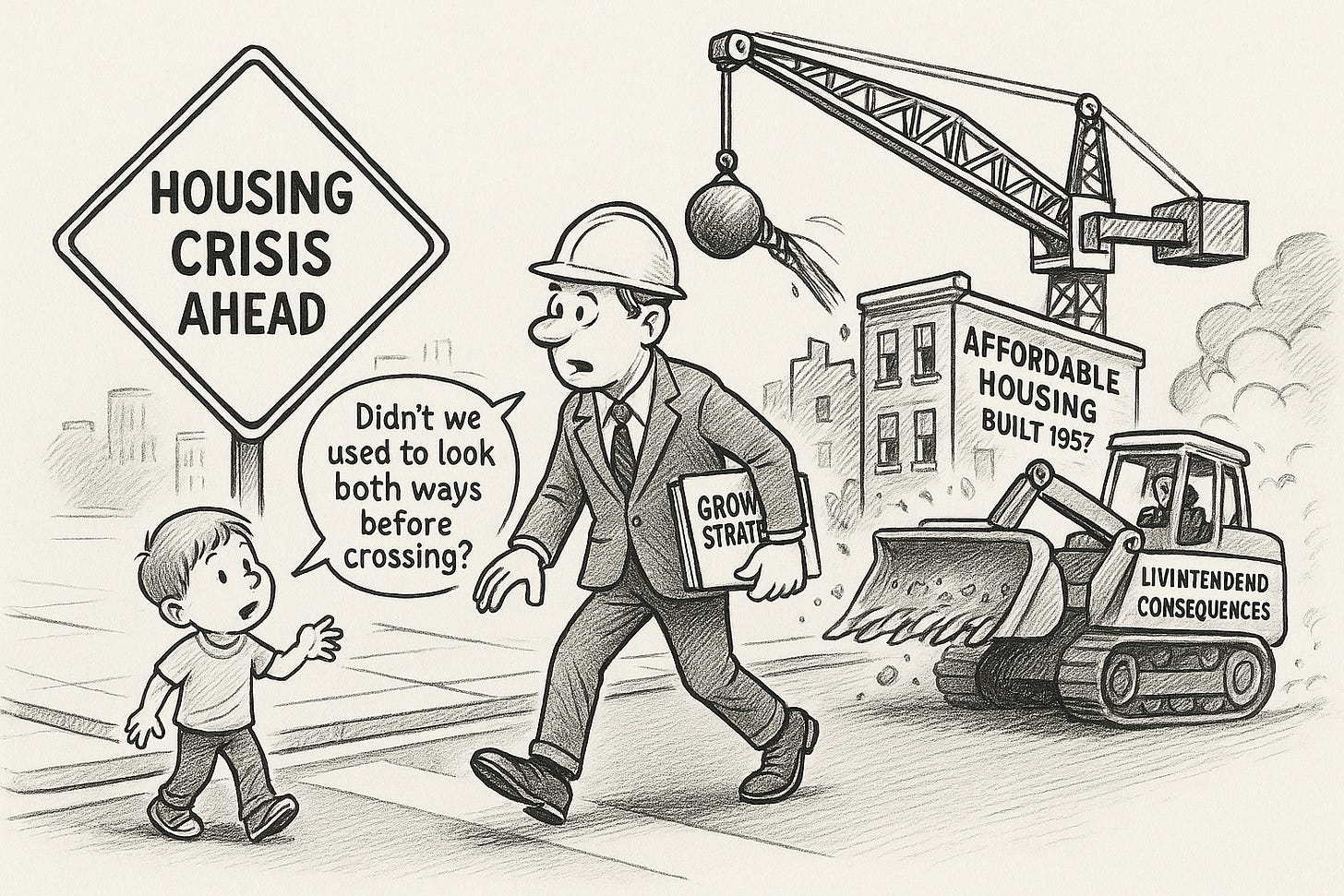

In a crisis, few want to look that far down the road. The housing crisis looms in the windshield, and we’ll worry about long-range possibilities later.

My instincts were set in motion before I was old enough to cross a street alone. Look both ways. In time, that wisdom became second nature. When a noisy vehicle approaches from one direction, check in the opposite direction before stepping into the street. Focusing only on the most obvious threat can blind one to subtle dangers unnoticed but for an ingrained habit.

We’ve been striving to build our way out of our housing crisis with such single-minded fervor that all failures to make progress are blamed on externalities—construction costs, tariffs, COVID, government revenue shortfalls, unforeseeable market shifts, etc.—and we never question the validity of our underlying assumptions.

Perhaps we need to look in the opposite direction. What if we just saved the housing units we have? We could incentivize the preservation of existing apartment buildings and houses, particularly the older and more modest ones likely to be lost without adequate maintenance? Or lost because developers see more profit potential in tearing them down and building something twice as big (and twice as expensive).

My ability to see what lies ahead may be no better than anyone else’s. For that reason, we should look in both directions before proceeding. Haven’t we always known that?

SDC's don't actually do anything about SYSTEMS; they help to finance the various permitting functions of government, pork-barrel projects, park expansion (which can't be maintained as the dopes on city council don't understand), and other progressive causes. If SDCs worked we wouldn't be looking at 100-percent increases in water and sewer rates.

The SDCs are an irritant, but the biggest new apartment "affordability" builds DO NOT pay SDCs. Nor do they pay property taxes, since they have been de facto socialized under the wings of nonprofit "ownership." Which is a much bigger scandal.