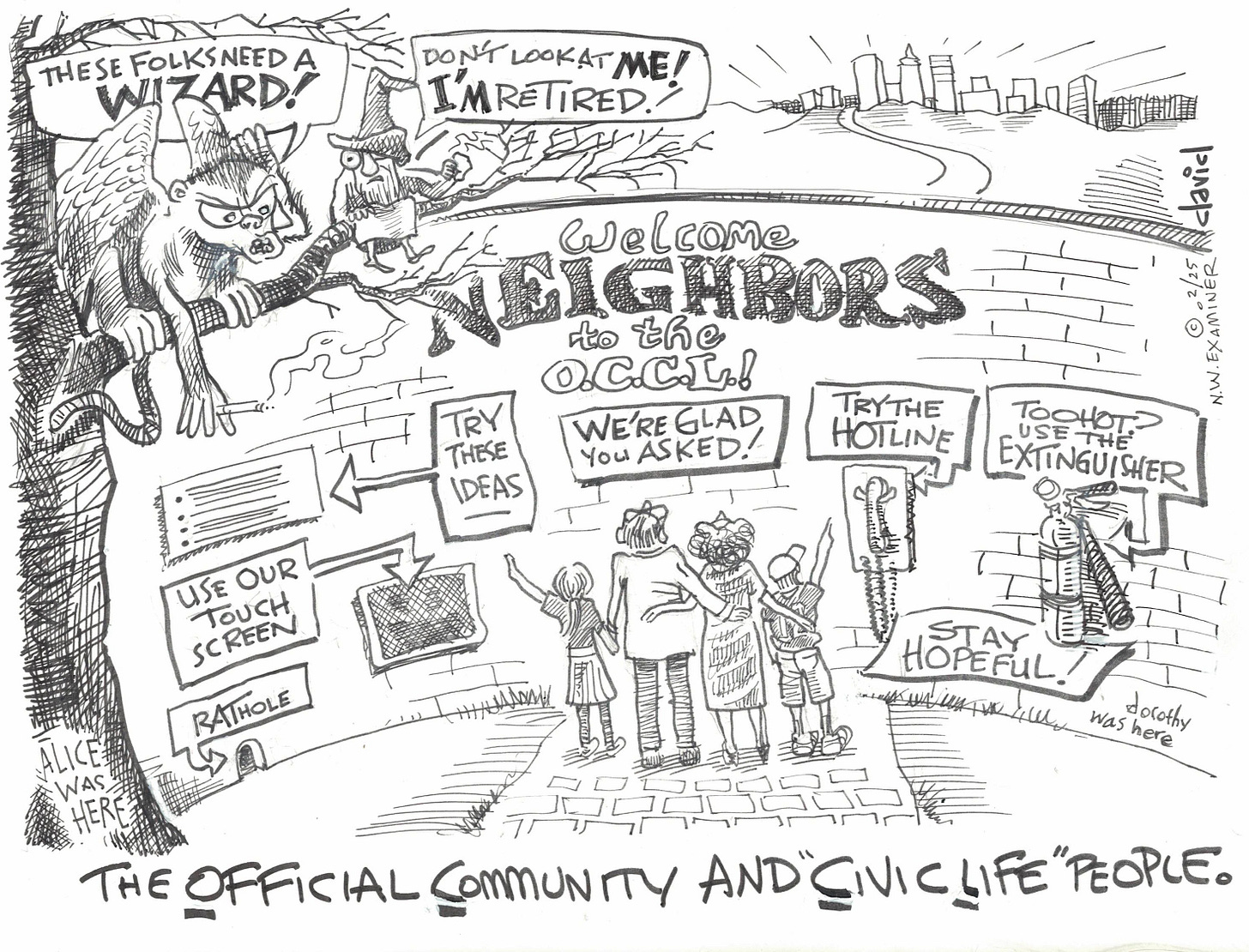

Lost on the yellow brick road

Our recently installed city officials are getting plenty of advice on the top issues facing Portland, but I have some observations on what’s going on at the lower end. That’s where the Portland renaissance took root during the Goldschmidt Era, as residents were encouraged to remain in the city by giving them a voice in shaping their neighborhoods, schoo…