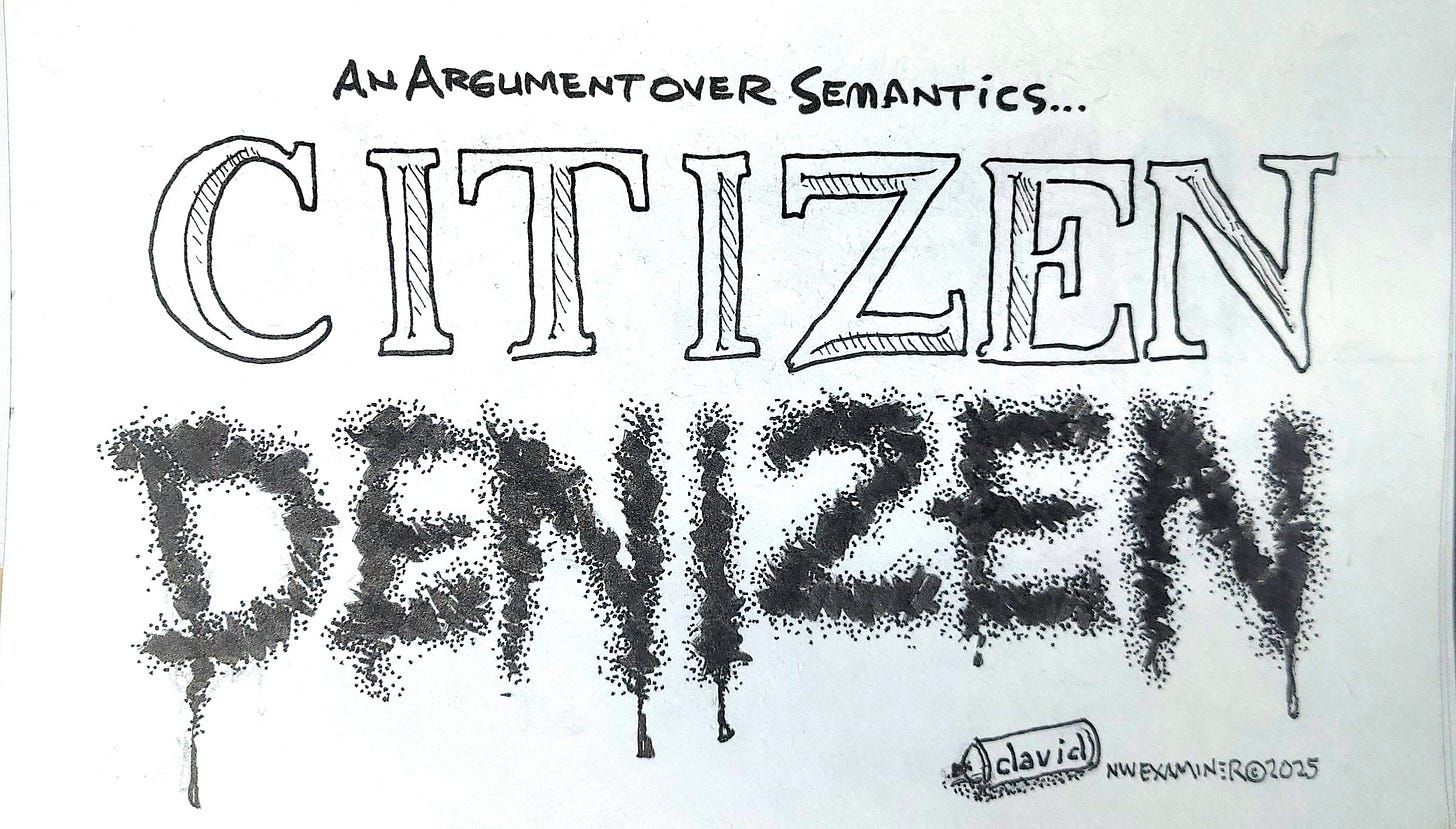

Is citizen a dirty word?

Some think they can improve upon it

When did citizen become a dirty word? For me, that jolt was delivered by Suk Rhee, the former director of the Portland Office of Neighborhood Involvement, which she helped rename Office of Community & Civic Life before being forced out of her position by a damning audit of her mismanagement.

Rhee was about a month into this position when we sat down for an hourlong talk for background only. By then, 2017, I had come to consider citizenship the highest calling for members of a democratic society—individuals taking responsibility for the welfare of their communities and society in general, doing their small or not-so-small part to spread a vision that benefits the whole.

It is no coincidence that many of the American founders were gardeners, the perfect metaphor for seeking pleasure in the thriving of living organisms. My first non-sports hero was Ralph Nader, who became known as the champion of consumers and then broadened his reach into founding Public Citizen, an organization protecting health, safety and democracy itself.

When I shared my views on citizenship, Rhee objected to the word. To her, citizenship involved the division between legal citizens and other inhabitants. Citizens are granted privileges not extended to noncitizens, and that was to her an unjust discrimination. She preferred “residents” or “members of the community” as more inclusive and appropriate terms.

She applied the most literal definition of citizen, while my mind was on a different plane. She advocated for the full rights of all regardless of legal status, and I was focused on the voluntary acceptance of responsibility to improve one’s community, the essence of neighborhood associations. The difference is immense. One demands rights for oneself or one’s group; the other asks, “How can we best live together?”

Rhee’s career may have hit a dip, but her view still shapes Civic Life, her former agency. Northwest District Association President Todd Zarnitz, along with two city employees, recently screened applicants to the stakeholder advisory committee that reviews parking policy in the district. Zarnitz was troubled to learn that candidates were filtered in favor of certain views and affiliations, but “we were not supposed to call them citizens.” Community members was the preferred term.

The goal of this newspeak is often described as social justice, frequently understood as correcting past injustices against certain groups. By uplifting the downtrodden, society will move toward equality (or equity, the preferred term today).

I would suggest a better way. Justice is not the supreme goal. Correcting injustice is merely the first step toward climbing out of the pit, the dog-eat-dog realm in which self-interest rules. Those who demand perfect justice as a prerequisite to cooperation and comity have a long, harsh winter of discontent ahead.

Shall we settle past scores and grievances, or bury the hatchet to build a better future together? That is not only the question for today but for all ages. It is the issue our founders got right.

The infamous Hatfields and McCoys feud of the 19th century ended after years of bloodshed, not because either side won that war or gained full redress but because they agreed coexistence was more precious than revenge. The feud lasted less than 30 years. Today the two clans hold joint reunions and celebrate their common history.

The Hatfields and McCoys are characterized as uneducated and violent, certainly not scholars of political philosophy or the humanities. Yet they found a way to rise above their enmity.

As Americans—a term I apply to citizens and other inhabitants who share our creed—we too can find a way … if we choose to.

Portland city government is short $100 million. The first step should be to close the Office of Civic Life. Second step STOP funding all nonprofits. Problem solved.

Good article--appalling, our leaders' civic ignorance and extremism-- even if the workplace behavior was not abusive. I suppose they have no idea of how radical they are.