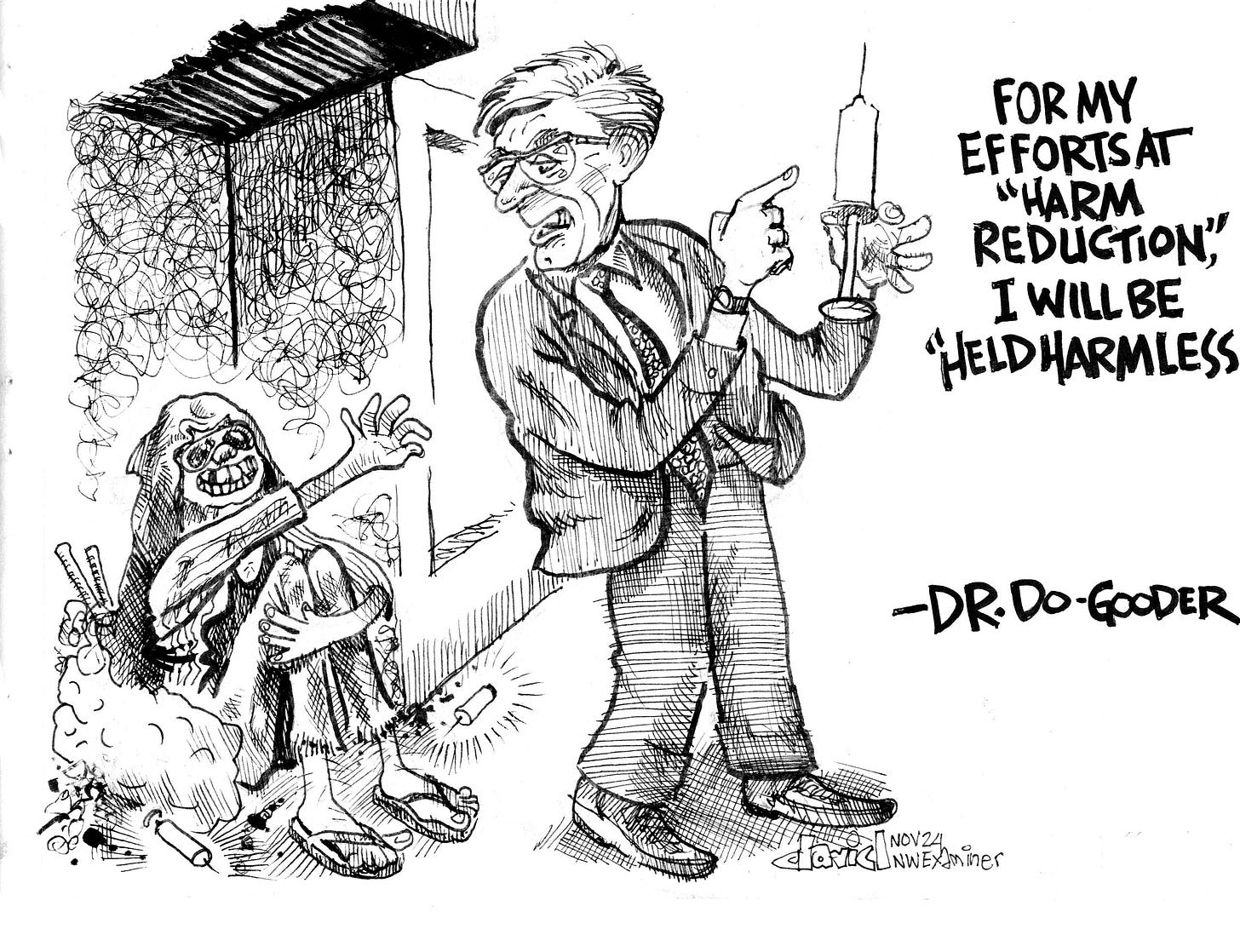

Harm reduction for whom?

EDITORIAL OPINION

Harm reduction for whom?

One cannot comprehend the political divide in Portland today without unpacking an approach known as harm reduction. The term gained attention last year when Multnomah County announced it would give tin foil and straws to fentanyl users so they could pursue their addictions more cleanly and conveniently.

Blowback w…