Creating purpose, finding recovery

The first step is crucial toward reaching a successful outcome

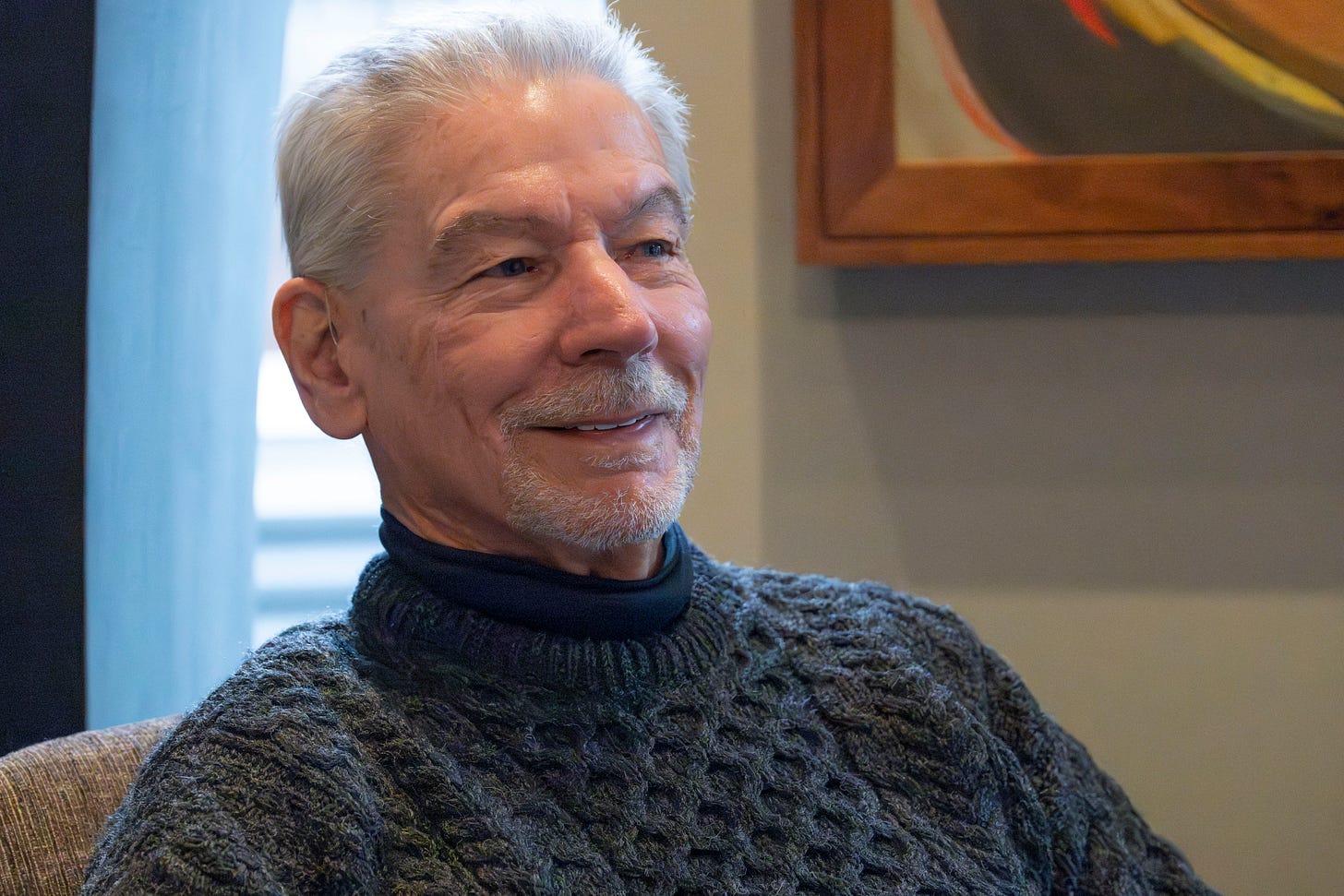

Dick Perkins confounds many who would put him on the spectrum of local attitudes on social issues. A former heroin addict and homeless person who later had a successful career in banking, he balances the needs of people suffering on the street with the interests of the wider community. He advises the Behavioral Health Resource Center and public officials on related issues.

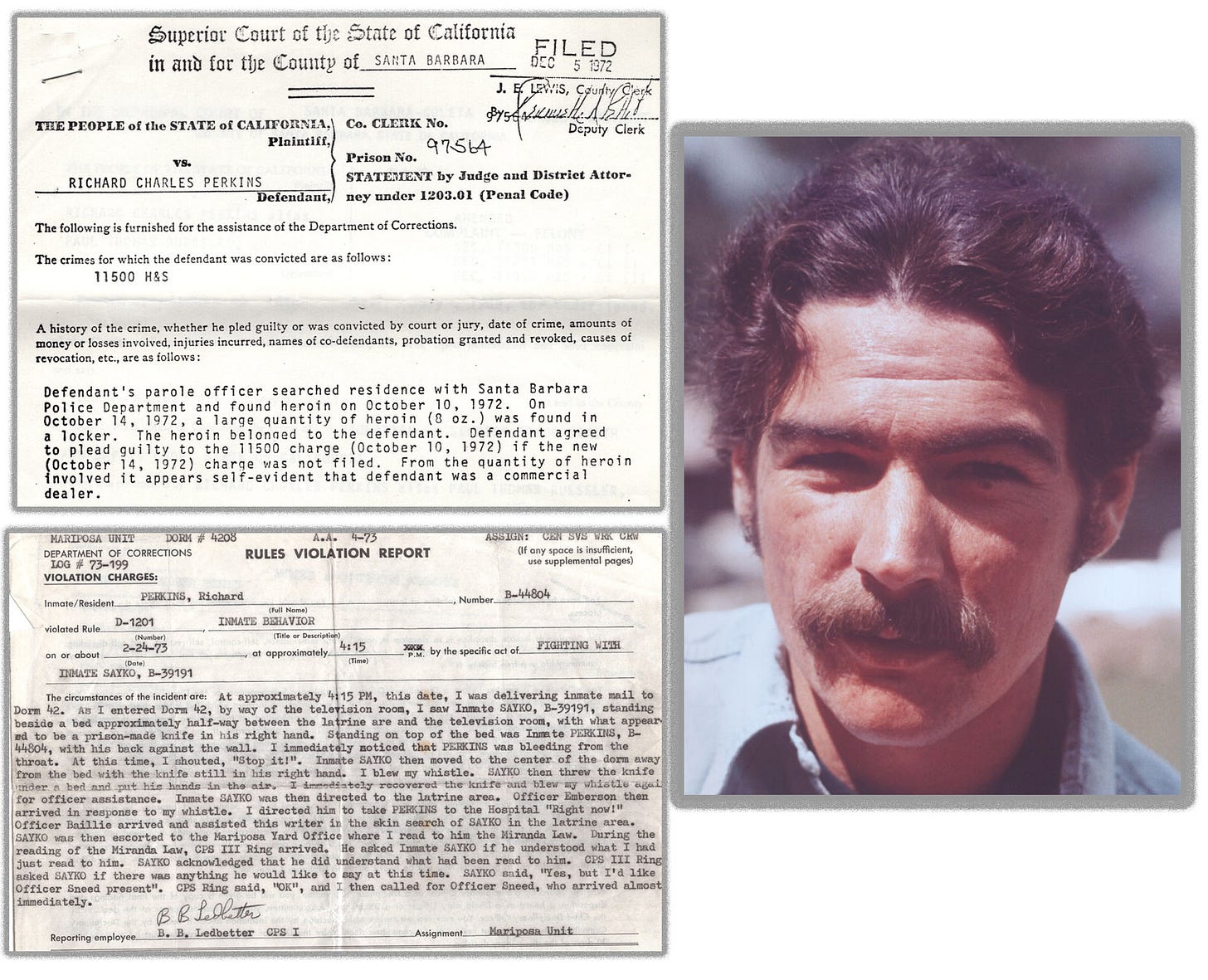

I’m a “recovered” heroin addict. Like all drug addicts, I needed to find useful purpose to recover. I am also a felon. I served three years in a California prison for possession of heroin. Before that, several stints in jail. Those were my drug detox opportunities. The time in prison with mostly fellow addicts, few like me demographically, taught me we had much in common: Drug addiction, lack of purpose and a violence-free record. And shared agency as addicts. We were lucky.

Today, over 50 years later, I share residence in downtown Portland with a plethora of addicts, mostly homeless. I’m well housed and retired from a career in commercial banking. I have some strong thoughts on purpose, recovery and the role of prison to share.

What is purpose?

It’s the thing an addict needs to start looking for after detoxing from the drug controlling them. It is why detox is so critical to start the process, because you can’t start looking until you are free from the compulsions the drug imposes.

The purpose is different for each of us. It evolves. It may be a newfound or rediscovered belief in God, the discovery of faith. It may be about reunification with loved ones you have wronged or disappointed. It may be to fit into a group you were shunned by. It may be a desire to “be your own person,” whatever that is. It may be a blank slate that appeals most, a fresh start, a clean slate. It is for all of us—a journey.

Purpose is as individual as we are as people. It is the thing we are best at but don’t realize it yet. It is what gives us self-gratification, what gives us approval from others and makes us feel as if we belong to something greater than just ourselves. It is something we are proud of, an achievement, a success. It is what gives us confidence and self-esteem without the need for drugs. It may be something we never found or something we found and lost.

Purpose can be as simple as a job or as wholesome as a calling, helping others or a promotion to a job you really want. It can be as fleeting as days sober or as permanent as recovery. It can be a series of positive steps forward or a final achievement. Pounds lost or a marathon run. It can be another “addiction” that you can better control; staying fit, eating well, working hard in your job, an insatiable curiosity for how things work, a passion for helping others. Or it can just be to live a life full of self-respect among folks you love.

Finding purpose starts with an assessment of your reality and proceeds with baby steps, a realistic vision for a future just days or maybe years hence, and a stepwise path toward that short- or long-term vision. It requires learning on the way and both flexibility and resolution to adapt and get there. You will learn new things about yourself that will change your vision, but it can’t change your determination to get to it. It requires learning to set goals for yourself and creating the determination to pursue them despite inevitable obstacles. It requires learning to celebrate the steps, even if the celebration is just in your mind. For your own self-esteem. Simply put, it’s learning how to set realistic goals to live by and growing those goals as you learn more about yourself, eventually leading to recovery. It is the process of recovering.

Oh, and finding purpose also means knowing what you don’t want to do as well. It means you understand the consequences of your decision to use drugs. It is accepting accountability for your decisions, no matter how strongly you want to blame those decisions on others. While you don’t yet know your future purpose, you know what will happen if you don’t find it. Detox again, start over. You own the consequences.

What is recovery?

Recovery (capitalized) is reached when you are comfortable enough in your purposeful life that you no longer must count the days sober. When your drug of choice is no longer an enticement to fear but just another thing you went through to get where you are. It is that simple. It is when you have created the basics of a life in society that is familiar enough that you would never consider throwing it away.

Most addicts will fail multiple times along the way and need to go through detox again. My experience tells me that each time, you stay sober a little longer, try a little harder and learn a little more about yourself and what purpose for you might be. In my case, prison was what I needed to finally get serious. I was lucky to have served time with drug addicts, not young gangbangers. I still had my throat slit in an unsuccessful attempt to kill me. My assailant died in San Quentin the next year. Prison is not designed for rehabilitation. It can easily work the other way. But it is accountability for decisions you have made. You must learn to accept it.

When I left prison, I was well on my way to recovery because I understood and survived the accountability society felt was appropriate. I knew I never wanted to go back to prison and that drugs would send me back. I had a plan; return to college, get a job, leave the temptation of Southern California and the lifestyle I grew up in and start a life where the only expectations I had to rise to were mine alone (and my parole officer’s). I had applied for college and student financial aid for those leaving prison before I was released, pending acceptance. I moved from my father’s home in Southern California to Arcata, in Northern California within three months of discharge, found a job as a maintenance manager for a quad apartment project near the Humboldt State campus and checked in with my new parole officer. I knew no one.

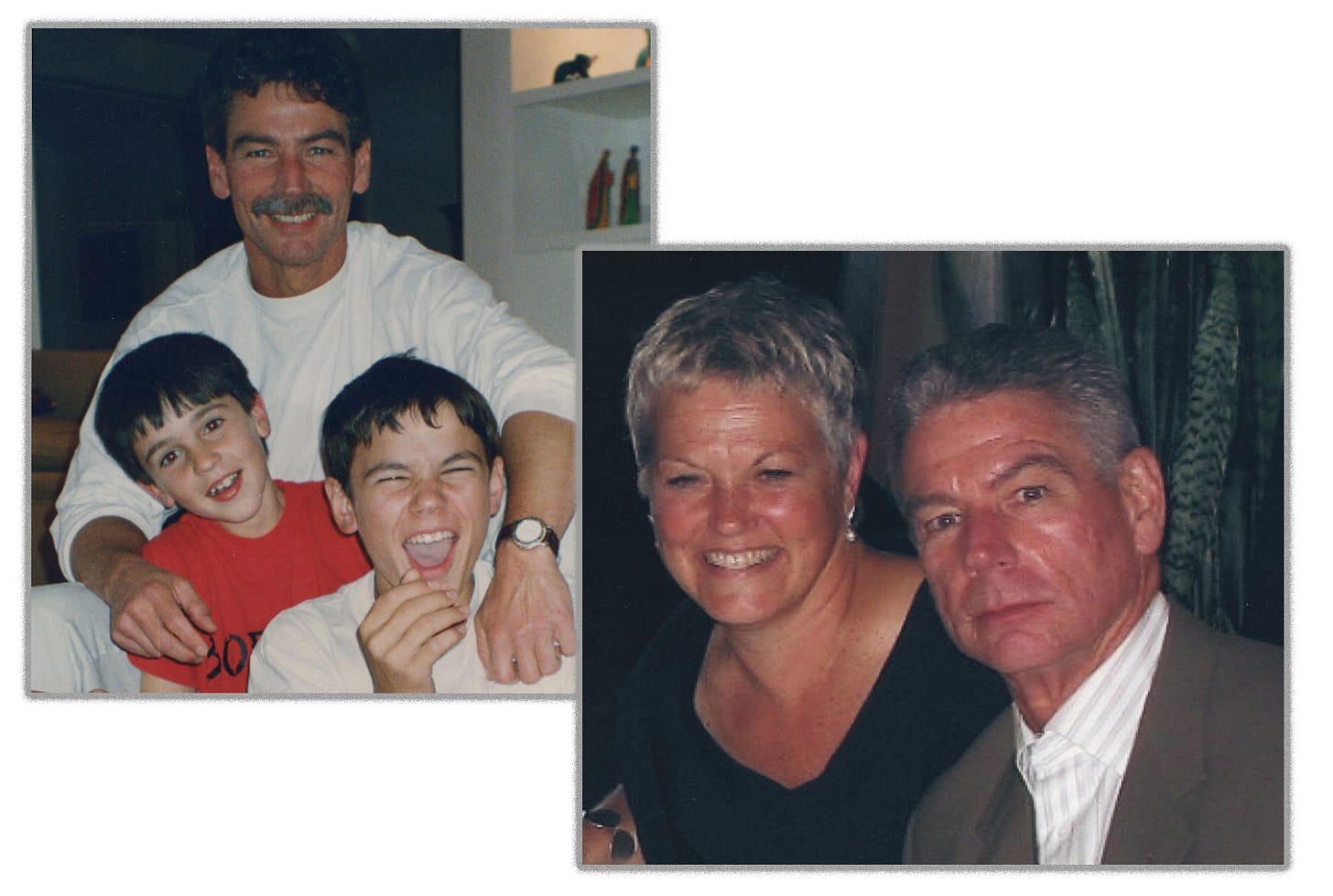

Luckily for me, the plan was realistic enough to work. I had attended college for two semesters after graduating high school, so I knew if I really attended classes and took it seriously this time, I would probably do ok. I did. My future wife was a quad mate. We adopted a cat. I traded maintenance work for teaching assistantships, was released from parole early, graduated and was accepted to graduate school at the University of Oregon, graduating from Humboldt State as I married my first wife. A series of little steps that built on the other.

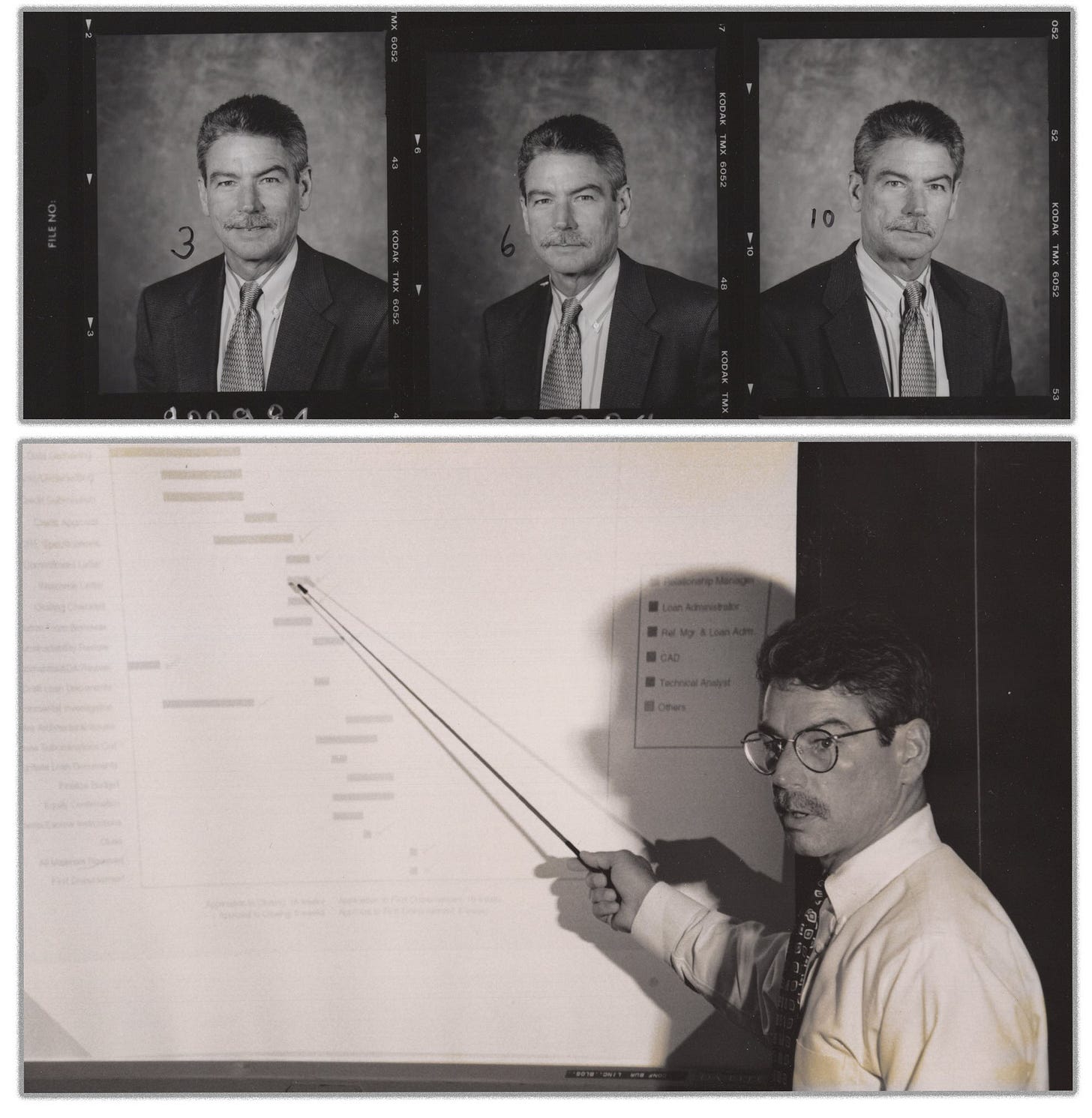

The plan changed many times over the years and there were plenty of setbacks and obstacles. A divorce, several layoffs and mergers, the suicide of my alcoholic father, moves around the country for work, my son’s deployment to Afghanistan and Iraq, crises with loved ones, my mother’s dementia and her death from it while in my care. I never had a career in urban and regional planning, in which I obtained a master’s degree. I was able to create a career in banking, where I had no formal training, created a network of bosses, fellow employees and clients and a positive reputation as a student, employee, mentor and manager and consultant without ever having to disclose my criminal past until late in my career. By that time, nobody cared. To be an executive officer of a de novo commercial bank, which I was, I needed Federal Regulatory approval and a full FBI background check, but by then, I had so many influential people who could attest to my character and my drug background became irrelevant. I had five major surgeries over the 50 years that required long recovery times. I controlled pain without addiction.

Times have changed

You may read this and conclude that it was so long ago, and that I am not typical of the addict on the street today. That my experience with purpose and recovery is irrelevant to the homeless fentanyl addicts we see on the streets of Portland. But nothing could be further from the truth. The drug has changed from heroin to fentanyl, making the addiction more intense and the recovery process more daunting, but the reasons for becoming addicted and the path to recovery remain the same. The obstacles today are identical; detoxing from the drug that controls you, so you have a chance to find a purpose unique to you, and through that, recovery. If I had not realized that I would have kept my little secret from the many friends I have made in Oregon, I would not be writing this.

My experience, combined with changing times, is why I favor a 30-day civil commitment for addicts rather than a criminal diversion. Most addicts will fail at least once, which means they will violate probation and be in jail serving the original sentence. This is not all bad, but they will need to contend with that criminal record the rest of their life, when applying for work or renting an apartment. The criminal record makes finding purpose and recovery that much more difficult. Today, anyone can pay a few bucks and look up your criminal record online.

Both mandatory jail time and civil commitment represent accountability and opportunities to recover because both give you a chance to detox from the drug that controls you, reflect on your life, get some support, plan, try and fail until you succeed. Given enough chances, most drug addicts will recover. The balance will end up spending most of their life in and out of jail or prison with stints on the streets until they OD, are killed or just waste away.

Lessons from recovery

Going home to friends and family to recover, especially when you have failed openly before, is not the best plan. Try as they might, friends and family expect you to fail again, and you can read that from them, no matter how much they try to hide it and how much they love you. My first thought when I heard the story of Rob and Nick Reiner.

Accountability is important, even if you accept that addiction is an illness. Unlike many illnesses, it can be cured. People recover. But they need help getting out from under the pervasive influence of their drug “of choice”. They need detox, voluntarily or involuntarily.

Tough love is helpful. My parents gave up on me. No attorney, no visits, even when in prison and even after my stabbing. If I wanted to reunite with them as an only child, it was up to me to prove myself. I was released to my father’s home pending college acceptance. His wife at the time refused to live in the same home, and I never met her.

Cold turkey detox is better than medically assisted detox, but it can’t be done voluntarily. It is intense, painful, long lasting and both psychological and physical. You think you are going to die. You do need to be medically supervised, but it won’t kill you. You will remember it when you get out and contemplate your next fix. From medically assisted detox with Suboxone or methadone, you remain addicted and coast through the withdrawals, only to be released with another addiction to kick and an appreciation of consequences.

While you can’t run from yourself, there is lot to say for a clean slate, some place where nobody knows you and you can create a far more positive and supportive network. You can always return to your family and old friends when you are recovered and comfortable in your own skin and solid in recovery.

Most addicts I interact with on the street in Portland today will need a lot of wraparound services, peer support, coaching and mentoring to be ready for housing and employment and social agency, much less recovery. Many have criminal records and wear facial tattoos that openly label them and restrict employment and housing options. They need sober housing with those wraparound services after detox, help with medical issues, educational achievement and criminal record expungement. Detox will represent less than 10% of their recovery time. The rest is up to them and the support network we provide.

In my experience testifying before the city and county over the last four years, it is the steadfast refusal by a few influential elected officials to make the Multnomah County drug addiction goal recovery instead of harm reduction that is to blame for the failures we see today. That is starting to change. So is resistance to mandatory detox.

I have been unable to persuade two local influential politicians who I believe can change the tide on behavioral health policy in Multnomah County. I have met with both. Both continue to resist the limited 30-day civil commitment proposal for those with hard drug addiction, but for slightly different reasons: Portland City Councilor Mitch Green of District 4 and Multnomah County Commissioner Meghan Moyer of District 1. I do not understand their resistance, nor have they shared with me their primary goals for those with addiction and their plan for achieving them, given the financial realities today.

It comes down to purpose. What is theirs? Let’s keep demanding answers.

Thank you for sharing your story and what you believe (and know) will lead to successful recovery.

It’s too bad the 2 elected officials you mention refuse to listen. Perhaps have they have not shared with you “their primary goals for those with addiction and their plan for achieving them” because they have none.

Portland prides itself on being a compassionate and inclusive community. Dick‘s testimony and recommendations seem like the tough love needed at this moment in time. What more can be done to help move the city forward?